[As published on The Barrister Magazine: http://www.barristermagazine.com/article-listing/current-issue/tackling-human-trafficking.html]

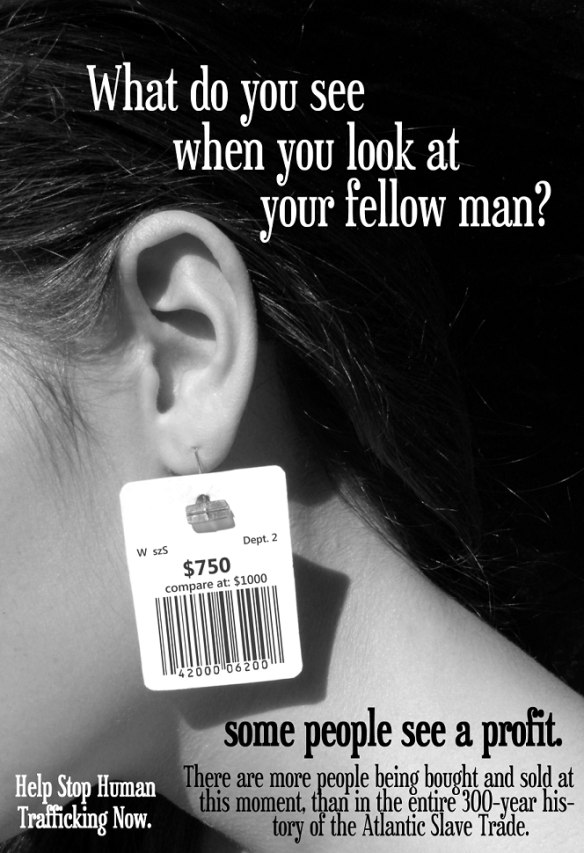

Recently human trafficking has returned in the UK media spotlight, as a study by the Centre of Social Justice has been published denouncing the Government’s failure to tackle this complex form of transational crime.

The internationally recognised definition of ‘human trafficking’ can be found in the Palermo Protocol (Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons, especially Women and Children) to the Convention against Transnational Organised Crime (the Protocol entered into force in 2003):

“Trafficking in persons” shall mean the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs… The consent of a victim of trafficking in persons to the intended exploitation set forth [above] shall be irrelevant where any of the means set forth [above] have been used.”

This complex definition seeks to capture the chain of trafficking which includes the act, the means to carry out the act and the purpose of the act. Therefore, the definition should be understood as follows:

1) The act: “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons”

2) The means: “by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person”

3) The purpose: “for the purpose of exploitation“. “Exploitation shall include, at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitution of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labour or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.”

It should be noted that, in each one of the three limbs of the definition, the elements listed are alternatives to be satisfied. Therefore, contrary to popular belief, a victim of human trafficking does not necessarily need to have ‘travelled’ or have been ‘transferred’. In fact, the mere recruitment is sufficient to satisfy the first limb of the definition – provided the subsequent other two limbs are satisfied too. Similarly, in the second limb of the definition, it is not necessary to prove that the victim was subjected to violence or threat of violence: other forms of coercion which satisfy the legal threshold, which are more of a psychological nature rather than physical, include the abuse of a position of vulnerability (e.g. an individual who offers to “help” an orphan). Finally, exploitation is commonly correlated to prostitution. In reality, the variety of forms of exploitation is far wider and includes the exploitation of individuals in cannabis factories, as well as in otherwise legitimate enterprises such as the textile industry (e.g. where workers are unpaid, paid under the minimum wage or made to work in unsafe and illegal conditions).

Of course, for human trafficking to be identified, all three limbs of the definition must be satisfied. This is the most complex aspect since one or more stages of the chain of human trafficking can easily be concealed. The greatest problem of this form of crime is the difficulty posed in identifying the victims and the crime itself. Often a victim might even be confused as a perpetrator, since the police might come across them for the first time in the context of the commission of a criminal offence, such as cultivating cannabis.

On 6 April 2013, the European Directive 2011/36/EU on Preventing and Combating Trafficking in Human Beings and Protecting its Victims will come into force in UK, meaning that that is the deadline by which the country must fully implement it. Some of the key changes that will be brought about by this welcome piece of legislation are requirements for/to:

- the establishment a dedicated national anti-slavery agency or Rapporteur

- the establishment of an EU Anti-Trafficking Coordinator

- increase public awareness of human trafficking

- set up special measures for the protection of victims and, in particular, of minors

- the revision of definitions relating to human trafficking offences to cover a broader range of cases, to include the commission of offences within the UK territory or by UK nationals outside of the UK territory

- the establishment of a system by which prosecution and punishment of defendants later identified as victims of human trafficking may be dropped where it is proven that their commission of criminal offences is correlated to their status as human trafficking victims.

The Crown Prosecution Service has recently published a new set of guidelines on Human Trafficking taking into account the European Directive soon coming into force. The UK needs to also work hard in cooperation with other EU Member States on raising awareness amongst officials dealing with immigrants, such as those at the UK Border Agency, as well as members of the criminal justice system including judges that all too often misunderstand the nature of this complex crime.

Source: The Guardian

Source: The Guardian